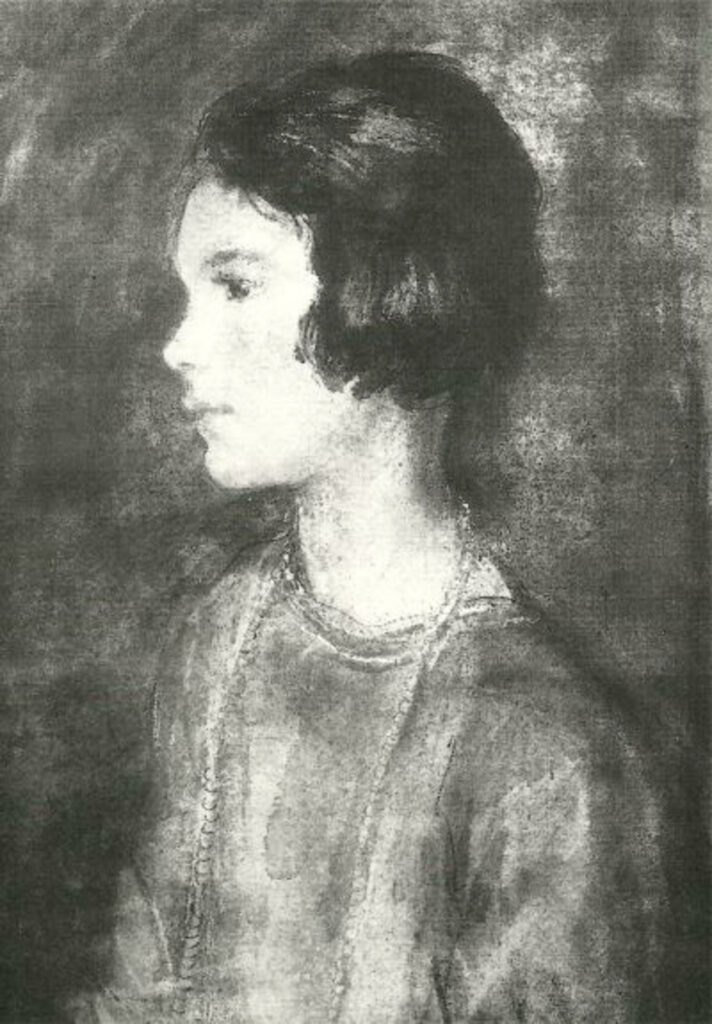

Elizabeth David CBE, née Gwynne, was born on Boxing Day 1913 to Stella and Rupert Gwynne at Wootton Manor near Eastbourne in Sussex, England. Elizabeth’s father was the Conservative MP for Eastbourne. Both her mother and her father came from prosperous and titled families, with descendants of English, Scottish, Welsh, Irish and Dutch roots. Elizabeth’s father was to become a junior minister in the government of Prime Minister Bonar Law. Elizabeth had three sisters: Priscilla, born 1909, Diana, born 1915 and Felicité, born 1917.

‘To eat figs off the tree in the very early morning, when they have been barely touched by the sun, is one of the exquisite pleasures of the Mediterranean’

Elizabeth David

Elizabeth David was, in many ways, a contradictory character. Born into an upper-middle-class family in Eastbourne, Sussex, England, she avoided the usual route of privileged young women of her time and initially opted for a far from conventional lifestyle. After her schooling, she lived on her own in London, working as an actress in the Regent’s Park Theatre and then, on the eve of the Second World War, embarked on an impulsive and dangerous adventure with her then lover, Charles Gibson Cowan, taking a barge through the canals of France to the Mediterranean, only to be arrested by the Italians as war broke out. In sharp contrast to this adventure, she was also happy to attend a French language and culture course at the Sorbonne, paid for by her mother, and to enjoy a privileged life during her short time living in Paris.

The enigma which is Elizabeth David can also be found in her romantic attachments; she never, ‘got her man’, rather she lost the love of her life, Peter Laing, in Cairo. Peter, who had been seriously wounded during the war, was forced to return as an invalid to his native Canada, thwarting her hopes of marriage. She then married a man to whom she was patently unsuited, Lieutenant Colonel Anthony David, and from whom she was soon separated. After a long struggle, she was finally able to divorce Anthony David after many years of estrangement.

Returning to England after becoming ill in New Delhi, she bought a house in Chelsea where she lived the rest of her life building her career as Britain’s most prominent food writer and cook.

She was careless about her health, she took little exercise, smoked and drank quite heavily and led a sedentary but stressful life. All this led to a stroke at a relatively early age. Her ill health was compounded by her frenetic work, writing constantly and her pedantic attitude to her publishers. She was easily enraged and did not tolerate fools gladly.

Below is a simple timeline of the key events in Elizabeth David’s life; it is meant as a general overview rather than an extensive study or detailed chronology of her life and work. In our Books section you will find two detailed biographies of Elizabeth David which tell her story in much more detail. You will also find a range of Elizabeth David’s cookery books and some of the published works of her friends and acquaintances.

Although Elizabeth was well cared for, her parents were far from overly affectionate and Elizabeth and her sisters were cared for by a nanny away from the main areas of the home, in the nursery. Elizabeth remembers the food the children were served as being plainly cooked, boring, often stodgy and even odious. Her one treat was when the nanny cooked field mushrooms and cream or garden fruit and sugar over the nursery fire. Her later interest in food can be traced back to her early days at Wootton.

When Elizabeth’s father, Rupert, died suddenly in 1924, Elizabeth and her sisters were sent to various boarding schools whilst her mother pursued her own interests, moving to Jamaica in 1933 and remarrying. When Elizabeth was sixteen, she was enrolled at the Sorbonne in Paris to undertake a course in French civilisation and culture, and it was here that she first experienced the joys and pleasures of continental cooking. After Paris, Elizabeth continued her studies in Munich, returning to England in 1932.

Elizabeth was eighteen when she returned to London and rejected the social norms of a young upper class woman. The life of a débutante did not appeal to her and she took up painting which she soon discarded in favour of acting. In 1933 she joined the Oxford Playhouse and a year later moved on to the Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre in London. She rented a room in a large house and for her twenty-first birthday bought a refrigerator and kitchen equipment. Her mother gave Elizabeth her first cookery book, ‘The Gentle Art of Cookery’, by Hilda Leyel. It was at this time that she became romantically involved with Charles Gibson Cowan, a married man nine years older than her, who had little time for social conventions. Cowan was an outsider; working class, left wing and rootless. Elizabeth’s mother thoroughly disapproved of Cowan and arranged for Elizabeth to spend time with family friends in Malta. However, in 1938, Elizabeth was back in London, ready to embark on a new adventure with Cowan.

Having found sufficient money, Elizabeth and Charles bought the ‘Evelyn Hope’, a wooden sailing boat with an engine, crossed the channel to France and sailed up the Seine to Paris. From Paris they continued, by canal and river, to Dijon and Marseilles, and finally to Antibes, where they were unable to gain permission to leave for six months due to the outbreak of war in September 1939.

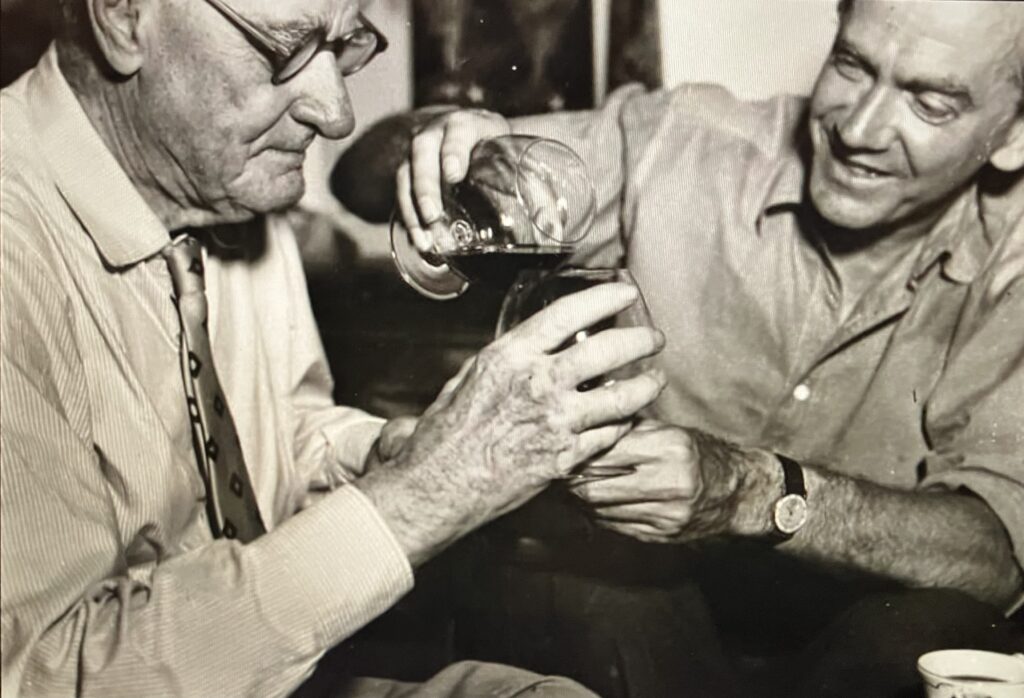

It was in Antibes that Elizabeth first met the writer Norman Douglas (pictured above, on the left, with Graham Greene.) Elizabeth was twenty-five and Norman was seventy but they immediately felt a great affinity for each other and there is little doubt that Norman became Elizabeth’s most important mentor. Norman taught Elizabeth to appreciate the Mediterranean and encouraged her in her love of good food, introducing her to many Mediterranean dishes, fruits and vegetables. They seemed to share a common view about life and Norman famously told Elizabeth to ‘search out the best, insist on it and reject all that is bogus and second-rate’.

In May 1940, hoping to visit Italy and Greece, Elizabeth and Charles set sail from Antibes to Corsica and then onwards towards Sicily. They had reached the Strait of Messina when, on 1oth June 1940, Italy declared war on the Allied nations. An Italian patrol boat intercepted the ‘Evelyn Hope’ and Elizabeth and Charles were arrested and escorted to Sicily. Charles was suspected of being a spy and the couple were interned for some nineteen days in various parts of Italy. During that time, they lost most of their possessions including Elizabeth’s notebooks, manuscripts and cherished collection of recipes. They were finally released and expelled to neutral Yugoslavia where they were able to gain new documents from the British consul in Zagreb and then crossed the border into Greece, arriving in Athens in July 1940. By this time, Elizabeth was no longer in love with Charles but they remained together out of necessity. Charles found a job teaching English and Elizabeth began to cook again using local produce and recipes. When the Germans invaded Greece in April 1941, the couple fled to Egypt.

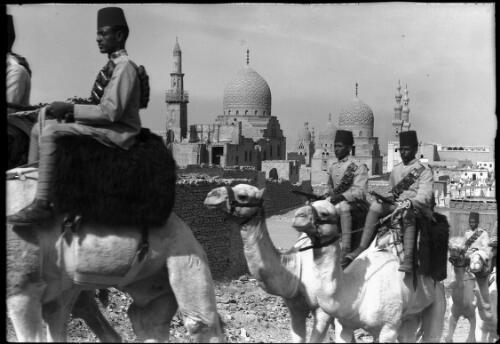

Although Charles wished to continue his relationship with Elizabeth, she wanted to enjoy the new life that awaited her in wartime Egypt. Speaking excellent French and German, she secured a job in the British naval cipher office in Alexandria and quickly found a most agreeable flat in the city. She engaged a cook called Kyriacou, a Greek refugee, who introduced her to new and delicious foods such as octopus stew in rich wine sauce with mountain herbs. She began to discover the foods and flavours of the Lavant. Kyriacou, although an excellent cook, was highly eccentric and a new cook, Suleiman, later took his place. Elizabeth remembers meals from this period; delicious spiced pilaffs, grilled lamb kebabs and the Egyptian dish ‘Fellahin’ which consisted of black beans, olive oil, lemon and hard-boiled eggs. In 1942 Elizabeth became ill and spent several weeks in hospital and felt obliged to resign from the cipher office. Upon her recovery, she moved to Cairo and set up a reference library for the British Ministry of Information. Through the library, Elizabeth met many interesting people and made new friendships. Her new friends included Alan Moorehead, Freya Stark, Bernard Spencer, Patrick Kinross, Olivia Manning and Lawrence Durrell.

During her time in Cairo, Elizabeth had a series of romantic attachments, falling in love with a young officer, Peter Laing, who she would have gladly married had he not been seriously wounded and forced to return to his native Canada. Reaching the age of thirty, Elizabeth felt she should find a husband and therefore accepted Lieutenant Colonel Anthony David’s proposal of marriage. They were married in Cairo on 30th August 1944 and within a year Anthony David had been posted to India. Elizabeth followed him early in 1946 but did not enjoy life in the British Raj. Suffering from severe sinusitis, Elizabeth returned to England in August 1946.

Returning to Britain after the warmth, abundance and good food of the Mediterranean and the Middle East, Elizabeth was daunted by the grey and drab Britain that she found. With rationing still enforced, people were still relying on wartime recipes and ingredients. The food she encountered was quite terrible. ‘There was flour and water soup seasoned solely with pepper; bread and gristle rissoles; dehydrated onions and carrots; corned beef toad in the hole. Need I go on!’ Elizabeth wrote. Whilst in London she met up with her former lover, George Lassalle, and they resumed their affair. In November of 1946, the couple decided to spend a week at a provincial hotel in Ross-on-Wye. This week spent in a bleak English backwater had a profound influence on Elizabeth and played a major part in the life she was to create for herself, cooking and writing about food that was almost unknown in post-war Britain of that time but which Elizabeth had enjoyed so fully in the previous six years.

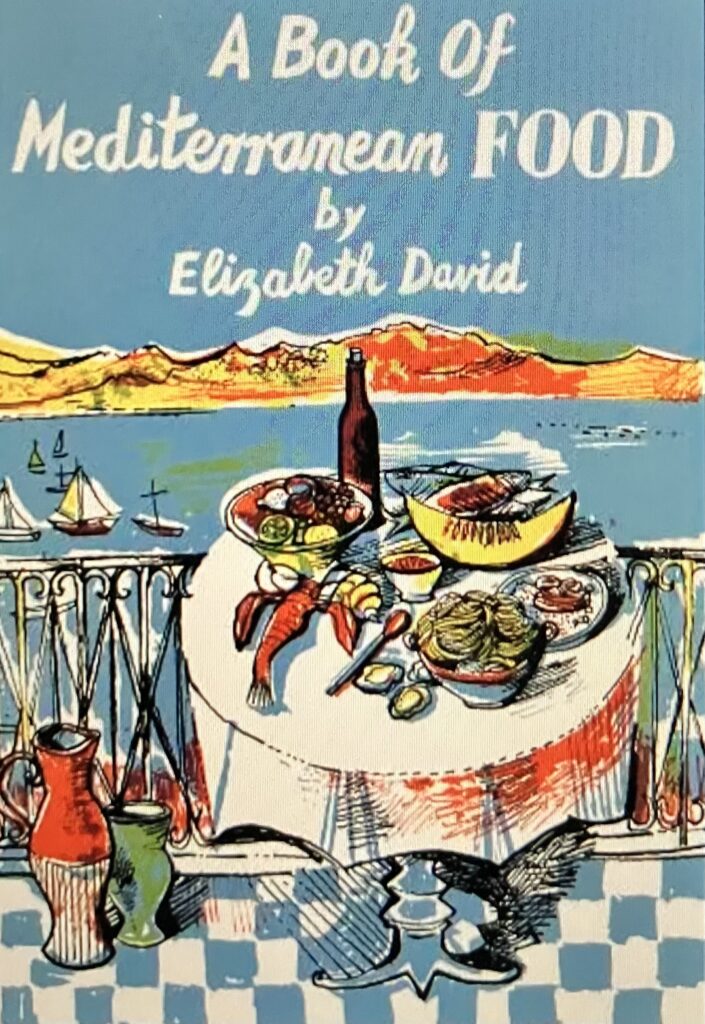

The experience of the hotel in Ross-on-Wye, the food austerity which was the hallmark of British cooking, her fond memories of the warmth of the Mediterranean, the extensive choice of fruits, vegetables, meats and delicious dishes that she had found in the Mediterranean and Middle East and that she now missed so much crystallised her thoughts. She began to make notes with the recipes she had collected on her travels and she became determined to write about better foods, ingredients and recipes. So it was that Elizabeth’s first article on Mediterranean food appeared in ‘Harper’s Bazaar’ in March 1949.

Elizabeth’s estranged husband, Anthony, had returned from India in 1947. At this point, Elizabeth separated from George and resumed her life with Anthony as his wife. With financial support from Stella Gwynne, Elizabeth and Anthony bought a house in Chelsea, London – 24 Halsey Street, where Elizabeth was to remain for the rest of her life. Anthony did not adjust well to civilian life, he was unable to find suitable work and ran up debts from a failed business venture. His relationship with Elizabeth deteriorated further so that, by 1948, they were living separately.

With the encouragement of a friend, Veronica Nicholson, Elizabeth continued to write articles for ‘Harper’s Bazaar’. As Elizabeth owned the copyright of these articles, Elizabeth began to put together the material for a book. Elizabeth submitted her manuscript to a number of publishers, all of whom turned her down. Revising her manuscript to include extensive quotes from established authors, she resubmitted the manuscript to John Lehmann, a publisher, and he accepted the work, with an advanced payment of £1oo. ‘A Book of Mediterranean Food’ with illustrations by John Minton, was published in June 1950. The book was generally very well received and Elizabeth Nicholas, writing in ‘The Sunday Times’, thought Elizabeth ‘a gastronome of rare integrity’. The success of the book led to offers of work from ‘The Sunday Times’ and ‘Wine and Food’, the journal of the Wine and Food Society. After a short holiday, Elizabeth settled back into her Chelsea home and invited her sister, Felicité, to move into the top flat of the house.

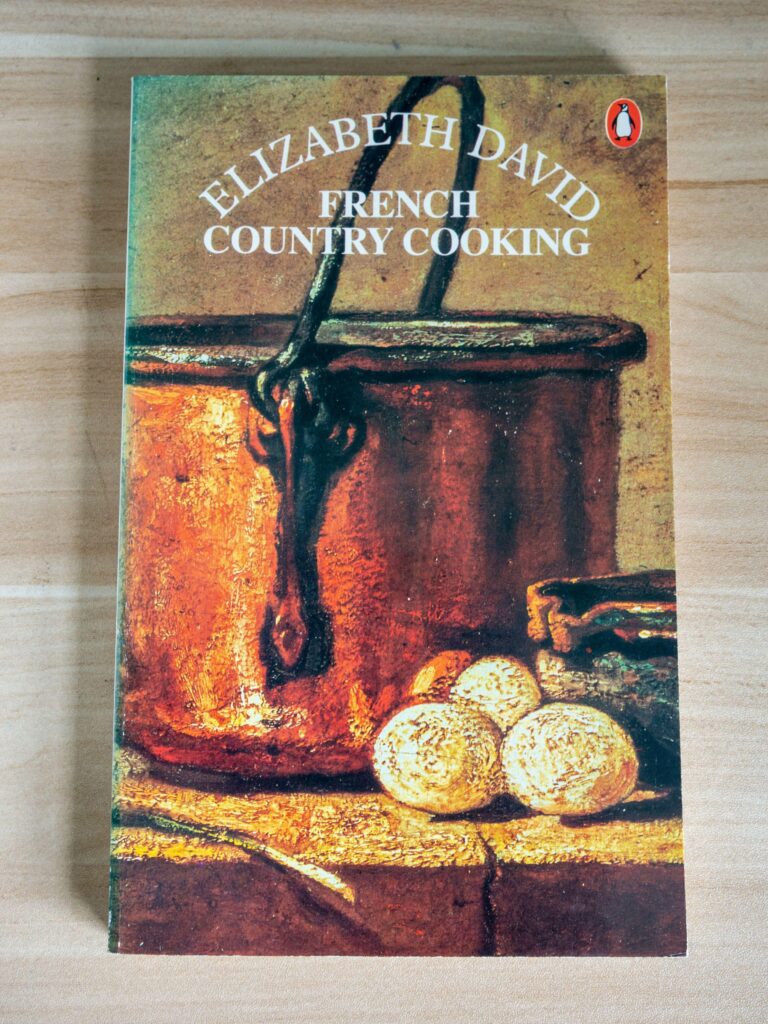

Following the success of ‘A Book of Mediterranean Food’, John Lehmann commissioned a second book which was to be ‘French Country Cooking’, again illustrated by John Minton and published in October 1950. Elizabeth then left England in March 1951 to spend three months in Provence. In June 1951 she travelled from Provence to Capri to visit Norman Douglas and after a whirlwind tour of the Italian Riviera returned to London. In September of that year ‘French Country Cooking’ was published and warmly received by critics. In Britain, interest in Italian cuisine was on the rise and Elizabeth and her publisher, John Lehmann, agreed that her next book should be on Italian food. With an advance of £300 pounds, she planned a visit to Italy where she also hoped to visit Norman Douglas; however, she was deeply saddened to learn of his death in February 1952. She left London in March 1952 and toured Italy, visiting restaurants, watching chefs at work and completing her research for her new book. In October 1952 she arrived back in London and rekindled a love affair with Peter Higgins whom she had met in India. This was a time of tremendous happiness for Elizabeth and gave her the confidence to continue her work. ‘Italian Food’, was published in November 1954, again to a warm reception. Evelyn Waugh named ‘Italian Food’ as ‘one of the two books that had given him the most pleasure in 1954’.

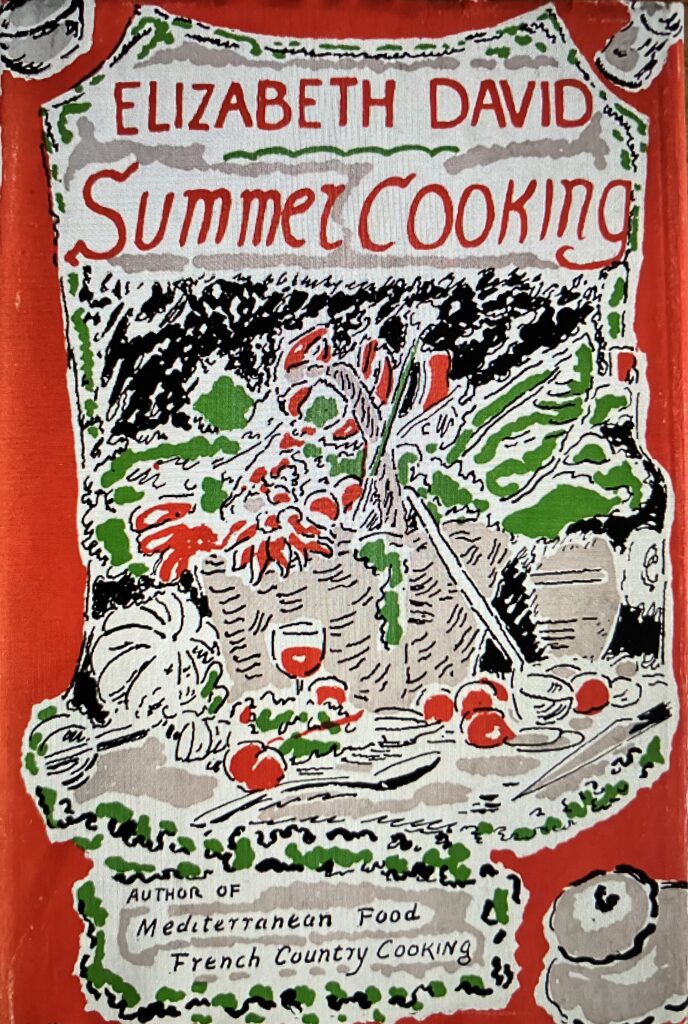

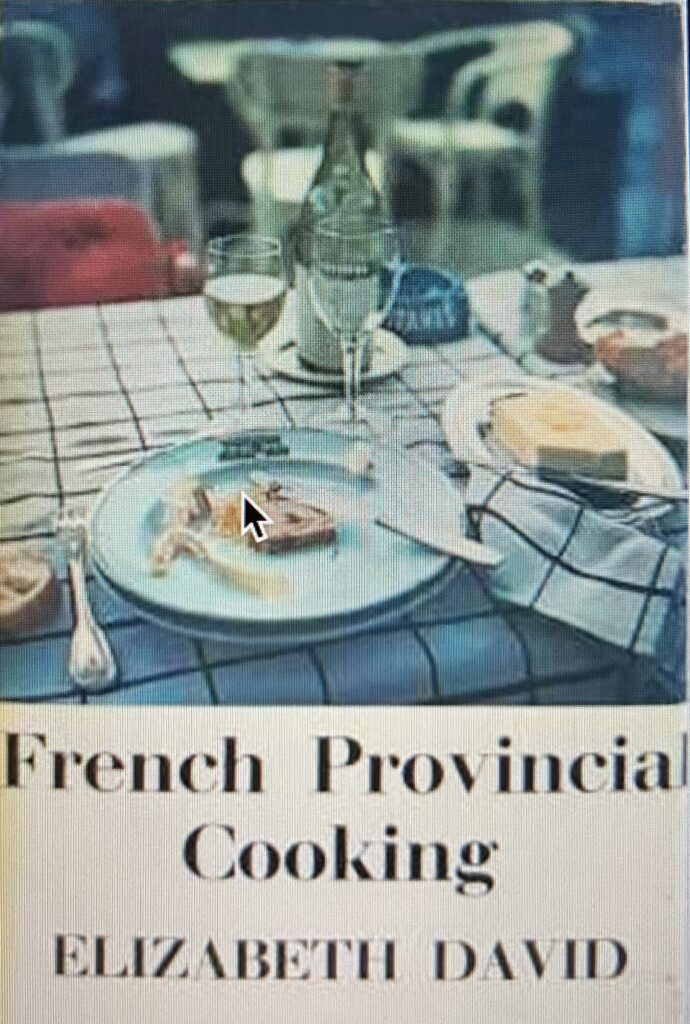

By 1954, John Lehmann’s publishing firm had been closed down and Elizabeth found herself contracted to Macdonald. She intensely disliked Macdonald and felt that they showed little care for her books and manuscripts. Elizabeth was able to persuade them to relinquish their option on her next book. Elizabeth sold her next book to Museum Press, which published ‘Summer Cooking’, illustrated by a friend of Elizabeth’s, Adrian Daintrey, in 1955. In ‘Summer Cooking’, Elizabeth wrote about dishes from around the world, including Britain, India, Russia, Turkey, France, Italy and Greece. The book reflected her strong belief in seasonal foods, which anticipated today’s rediscovery of the importance of seasonality in the use of ingredients. Soon after the publication of ‘Summer Cooking’, Elizabeth started writing for ‘Vogue’ magazine, which offered her a prominent full central page as well as a full-page photograph. The new contract also enabled her to write for the sister magazine of ‘Vogue’, ‘House & Garden’. ‘Vogue’ provided her with funds to undertake new research in France which led to her next book, ‘French Provincial Cooking’, which was published in 1960. ‘French Provincial Cooking’ was the culmination of over ten years work and ran to 600 pages, establishing Elizabeth’s reputation as not only a cook but as a writer of excellence. ‘The Observer’ spoke of Elizabeth as having ‘a very special kind of genius’. The publication of ‘French Provincial Cooking’ coincided with Elizabeth’s long delayed divorce from Anthony David in 1960.

In 1960, Elizabeth ceased to write for ‘The Sunday Times’ and ‘Vogue’, joining instead ‘The Spectator’, ‘The Sunday Despatch’ and ‘The Sunday Telegraph’, writing weekly for these publications. She enjoyed far more editorial freedom and had become a voice of authority following the publication of ‘French Provincial Cooking’. Her books were now published for the mass market by Penguin Books, who had sold over a million copies by 1985. Derek Cooper considered that Elizabeth’s ‘professional career was at its height. She was hailed not only as Britain’s foremost writer on food and cookery, but as the woman who had transformed the eating habits of middle-class England’. The peak of her success coincided with a number of personal misfortunes. Her affair with Higgins came to an abrupt end in April 1963 when he remarried. Elizabeth was devastated and began drinking excessive amounts of brandy and took sleeping pills on a regular basis. Elizabeth was also tired from her work and took little, if any, exercise and indeed took little care of herself generally. Consequentially, in 1963, Elizabeth suffered a stroke which was kept hidden from her publishers and the public at large. She recovered but her confidence was shaken and, for a period, her sense of taste was affected and she became nauseous at the smell of frying onions.

In November 1965, together with four business partners, Elizabeth opened a shop in Pimlico called ‘Elizabeth David Ltd’, selling kitchen equipment, much of which was imported from France. Elizabeth was tasked with selecting stock and often refused to stock items she deemed to be of no use in a kitchen despite considerable demand from the public. A good example of this are garlic presses, which Elizabeth considered to be, ‘utterly useless’. In order to devote more time to the shop, Elizabeth cut back on her writing commitments and began to focus on her writing on English cuisine. She rebelled against many, then modern developments in cooking, including mass-produced white bread, the use of the word ‘crispy’ instead of ‘crisp’ and railed against fussy garnishing as well as cheap pizza and the modern ‘Welsh rarebit’ as opposed to the traditional form of ‘Welsh rabbit.’ Whilst still running the shop, she produced another full-length book, ‘Spices, Salt and Aromatics in the English Kitchen’, published in 1970.

Elizabeth’s purist attitude to the shop was at odds with her business partners’ commercial acumen and their desire to run the shop profitably. Tensions between Elizabeth and her partners were high and the shop was not a commercial success. Elizabeth’s disagreements with her business partners, the suicide of her sister Diana in March 1971, as well as the death of her mother in 1973, contributed to a number of serious health problems for Elizabeth. In 1973 she resigned from the company and the shop. She hoped her business partners would change the trading name of the shop but they refused and this caused Elizabeth considerable stress for the rest of her life. Despite her health problems and her excessive workload, Elizabeth was able to publish a new book, ‘English Bread and Yeast Cookery’, in 1977. In the same year Elizabeth was badly injured in a car accident and spent some time recovering in hospital. The book, however, received glowing praise from Jane Grigson in ‘The Times Literary Supplement’, where she suggested that every married couple should be given a copy. ‘The Observer’ remarked that the book was ‘a scathing indictment of the British bread industry’.

Jill Norman, who was to become Elizabeth’s literary executor, had undertaken research for Elizabeth’s book, ‘English Bread and Yeast Cookery’. Elizabeth and Jill decided to continue their collaboration and to produce two further books, one on ice and ices, and the second a collection of Elizabeth’s early journalism. The book on ice and ices required considerable research and was not published until after Elizabeth’s death, having been completed and edited by Jill and published as ‘Harvest of the Cold Months’. The book of existing essays and press articles took less time to prepare and was published in 1984, under the title, ‘An Omelette and a Glass of Wine’. In 1986, Elizabeth’s contribution to British cooking culture was recognised when she was awarded a CBE.

In 1986, Elizabeth’s sister, Felicité, who had lived with Elizabeth for thirty years, died. Elizabeth began to suffer from depression and chest pains and spent three months in hospital. At this point, Gerald Asher, a wine importer and friend of Elizabeth’s, invited her to stay with him in California in order to recuperate. Elizabeth made several visits to California which she enjoyed very much. However, her health continued to fail as she suffered a succession of falls and was hospitalised on several occasions. In May 1992, Elizabeth suffered a stroke and two days later another stroke which proved to be fatal. Elizabeth died at her Chelsea home on 22nd May 1992, aged 78. Elizabeth was buried on 28th May at the Church of St Peter ad Vincula in Folkington, close to the original family home where she was born. In September 1992, the memorial service was held at St Martin-in-the-Fields, London.