Elizabeth David and George Orwell

Posted on Fri 20th December, 2024 by Elizabeth David Matters – editorial team

Elizabeth David and George Orwell are not writers one usually associates with each other; they came from quite different backgrounds, they had very different lives and there was little if any synergy in their interests and the causes they advocated and sought to advance.

When Elizabeth David found herself in a less than agreeable hotel in Ross-on-Wye with her then lover, George Lassalle, in the winter of 1946, her thoughts were on the food, drink and culture of the Mediterranean and the Middle East as she contemplated the dire food served to her by the hotel and in British catering establishments generally. Such was her abhorrence of British cooking, its limited range of foods, poor preparation and the general culture, or rather lack of culture, of eating, that she set herself the task of redefining the food interests and tastes of the nation with her first publication, ‘A Book of Mediterranean food’, of 1950. This book sent seismic shock waves through the psyche of British food producers, food suppliers, cooks, chefs, restaurants and hotels, and, not least, the British public.

David had found herself in a culinary ‘desert’, in a wet and drab Britain. The hotel food was almost inedible and the local shop offered nothing that tempted her palate.

Post-war Britain was a patient in recovery. The war years had led to a ‘make do and mend’ culture and food was a fuel for work and survival rather than a delight for the taste buds. Rationing continued until 1953 and the nation had reverted to a punitive food culture based on the supply of foods produced on the British Isles; a wet, cool to cold climate, bereft of sun for much of the year.

David could not have returned to Britain at a worse time in terms of food availability and the range and quality of the meals served in restaurants and hotels. It was natural that she, as an energetic and ‘no-nonsense’ young woman should rebel against the travesty of the culinary ‘arts’, which was British food in 1949. She longed for the spices, fruits and vegetables, the olive oil, the varied fish and meats of the Mediterranean and Middle East which were almost entirely absent in Britain.

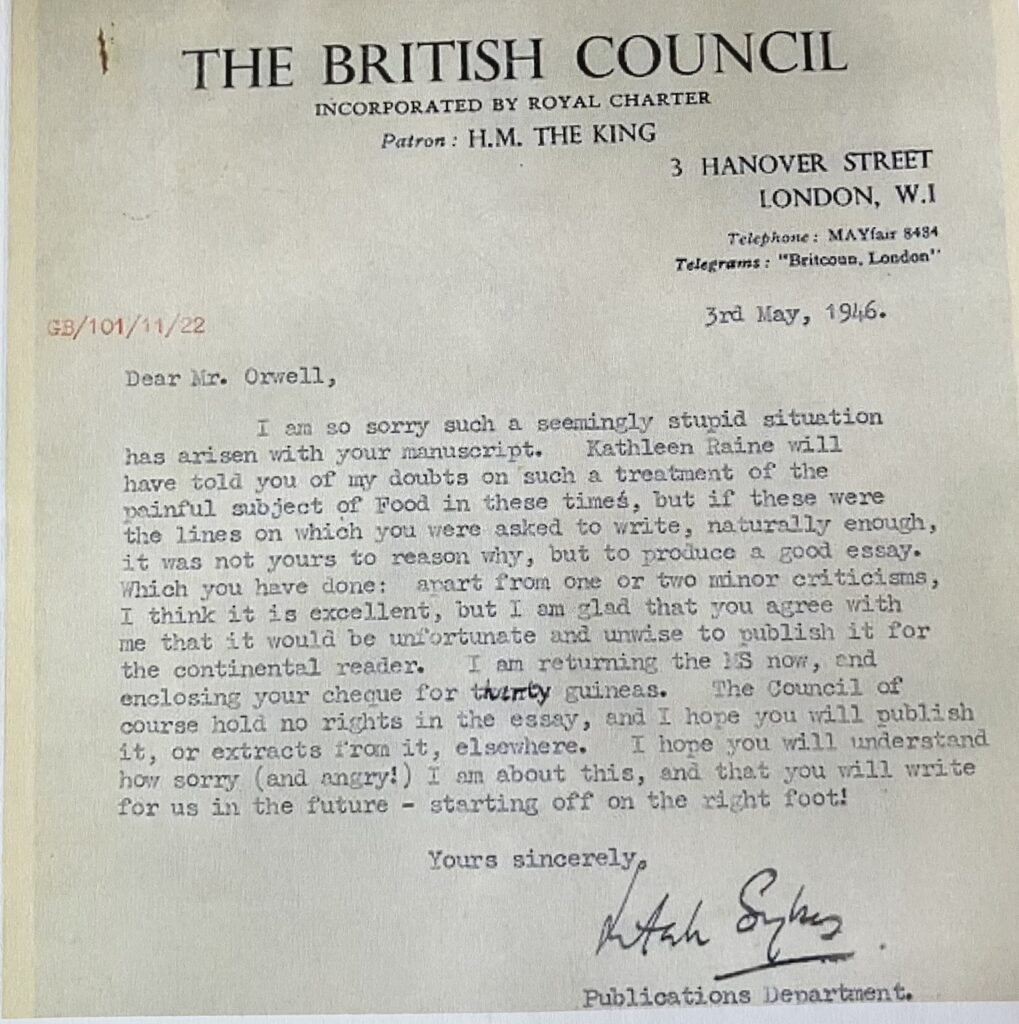

So what was British cookery in 1946? What were the main foods on which the people of Britain survived and what were the dishes served across the nation in the homes of the British people? To answer these questions one cannot do better than to refer to two essays by George Orwell. ‘In Defence of English Cooking’, a very short essay, was first published in December 1945 in the ‘Evening Standard’ and since 1984 has been available in a Penguin book of that name. In 1946, George Orwell was commissioned by the British Council to write another essay on British cookery which was intended to be distributed overseas. Orwell produced the essay and was paid his royalty fee by the British Council. However, the British Council felt that it would be ‘unfortunate and unwise to publish it (the essay) for the continental reader’, and the essay remained unpublished.

The British Council, in 1946, found the subject of British food ‘painful’

Orwell argued that British restaurants almost inevitably served French or imitation French foods, usually of bad quality. He contrasted this with the meals British people cooked for themselves and ate at home. Orwell stated that ‘one may say that the characteristic British diet is simple, rather heavy, perhaps slightly barbarous, drawing much of its virtue from the excellence of local materials, and with its main emphasis on sugar and animal fats.’

In his 1946 essay, Orwell spends much time discussing the different times that meals are taken and indeed the nomenclature of the meals themselves according to class. He states that breakfast is ‘not a snack, but a serious meal’, which, regardless of class, is usually taken at nine o’clock except when work dictates an earlier hour. Orwell continues by defining lunch as a meal taken by the middle classes whereas that same meal would be called ‘dinner’ by the working class. Further on in the daily timetable of meals, Orwell states that the working class call their evening meal ‘tea’ which they generally eat at half past six, whereas the middle class have a more substantial meal, which they call ‘dinner’, at seven thirty or eight o’clock. The working class finish their day with a light snack called ‘supper’. Orwell also notes that the time and name of the meals is not only derived from class but from regional variations as well.

‘It is commonly said, even by the English themselves, that English cooking is the worst in the world’

George Orwell

In describing a typical English breakfast, Orwell refers to this as a ‘meal consisting of three courses, one of which is usually a meat course’. To start with, Orwell suggests that porridge is to be served together with cold milk or cream and sugar. As an alternative, he suggests readily prepared breakfast cereals. For the second course, Orwell suggests that ‘the kipper’ is often served, this being a herring split open and cured in wood smoke until it is deep brown in colour. As an alternative, breakfast meat dishes consist of fried bacon, with or without eggs, grilled kidneys, fried pork sausage or cold ham. Orwell also refers to a less modern meat course of grilled beefsteaks or mutton chops and even cold roast beef. Orwell also notes that in East Anglia, cheese is often served at breakfast. The third breakfast course is bread, or more often toast, served with butter and orange marmalade. Tea is the most popular drink at breakfast, Indian tea being preferred over Chinese tea.

For lunch or dinner according to class, Orwell states that the meal usually consists of a roast meat and a heavy pudding followed by cheese. The ‘joint’ Orwell describes as a large piece of meat, roasted whole with potatoes. Beef is served with Yorkshire pudding and horseradish sauce. Pork is served with apple sauce and mutton served with mint sauce. A roast fowl is served with bread sauce, itself made from white breadcrumbs, milk and onions. Orwell also describes British puddings as an alternative to the ‘joint’. He describes steak and kidney pudding, which is made with chopped beef steak and sheep’s kidneys encased in a suet crust and steamed in a basin. Another alternative is Toad-in-the-Hole, where sausages are embedded in a Yorkshire pudding-like mixture and baked in an oven. Finally, Orwell describes cottage pie as flavoured with onions and covered with layers of mashed potato and baked in an oven. As a token to Scottish cooking, Orwell describes the Haggis, in which liver, oatmeal, onions and other ingredients are chopped fine and cooked in the stomach of a sheep.

‘The two great shortcomings of British cookery are the failure to treat vegetables with due seriousness, and an excessive use of sugar’

George Orwell

Although an island nation, Orwell notes that fish in Britain is seldom well cooked and the art of seasoning fish not well understood. Orwell rails against what we today would call ‘fish and chips’, which he describes as ‘definitely nasty’ and a food to which the working classes are addicted due to its low price and easy availability. Orwell comments that freshwater fish is rarely eaten in Britain with the exception of eels and trout. As for vegetables, Orwell believes that they seldom get the treatment they deserve while cabbage is simply boiled until it is ‘almost uneatable’ and salad is notably absent from the British table.

Orwell considers suet as a mainstay of British cooking, be it as a savoury used to make various meat puddings or as a sweet used to make roly-poly pudding and boiled apple dumplings. Although Orwell does not generally find British pastry appealing, he singles out for praise both treacle tart and mince pies. Continuing on the theme of puddings, Orwell notes that there are many types of milk puddings to be found in British cuisine. He lists rice, semolina, barley, sago and macaroni as ubiquitous staples which when mixed with milk and sugar are then baked in the oven. These puddings, Orwell contends, are inexpensive and easy to make and often served in cheap hotels and restaurants as well as lodging houses. Orwell believes that these milk puddings are one of the chief reasons why British cookery has such a bad name amongst foreign visitors. He singles out macaroni pudding as being ‘intolerable to any civilised palate’.

Orwell recounts that most cheeses found in Britain are of foreign origin and the quantities of British cheese produced are quite low and consumed locally. He considers the best British cheeses to be Stilton and Wensleydale.

Orwell confidently describes the foods available and the nature of British cooking which Elizabeth David encountered upon her return to Britain in 1946. Given that Orwell’s essays were commissioned to promote the virtues of British food and British cooking, even his best efforts to extol the virtues of certain foods and preparations fall short of what one might call fulsome praise. It is in this culinary environment that Elizabeth David found herself and which evoked in her a great desire to bring to these island shores the variety, flavour, texture and quality of those foods which she had grown accustomed to in the Mediterranean and Middle East. For Elizabeth David, British cooking needed a revolution and a supply of hitherto unavailable produce in order to restore British cuisine to a status equal to that of continental Europe and the Mediterranean.

‘No one who has not sampled Devonshire cream, stilton cheese, crumpets, potato cakes, saffron buns, Dublin prawns, apple dumplings, pickled walnuts, steak and kidney pudding and, of course, roast sirloin of beef with Yorkshire pudding, roast potatoes and horseradish sauce, can be said to have given British cookery a fair trial’

George Orwell